DOWNLOAD

Submit the form below to continue your download

SUCCESS

Your download will begin shortly, if it does not start automatically, click the button below to download now.

DownloadBIO

David Crane is the CEO and Chairman of the Board of Generate Capital, a leading sustainable infrastructure platform delivering affordable, reliable resource solutions to companies, communities, and cities.

Prior to Generate, David served as CEO of five publicly traded energy companies and as Chair of three: NRG Energy, NRG Yield, Climate Real Impact Solutions I&II, and International Power Plc. During his 12 years at NRG Energy, David led the company from Chapter 11 to a Fortune 200 company. He is a frequent speaker on opportunities for accelerating the energy transition and was named the Energy Industry “CEO of the Year” by EnergyBiz in 2010, top CEO in the electric utility sector by Institutional Investor in 2011, and “Entrepreneur of the Year” by Ernst & Young in 2010. Prior to Generate, he served as Under Secretary for Infrastructure at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). David has previously served on the Boards of Heliogen Inc, Source Global, JERA Co. Inc., Saudi Electric Company, ACWA Power, El Paso and Tata Steel Ltd. He is a graduate of Harvard Law School and Princeton University.

Consolidation: The Pathway to Enduring Impact

Expert View By David Crane

BIO

David Crane is the CEO and Chairman of the Board of Generate Capital, a leading sustainable infrastructure platform delivering affordable, reliable resource solutions to companies, communities, and cities.

Prior to Generate, David served as CEO of five publicly traded energy companies and as Chair of three: NRG Energy, NRG Yield, Climate Real Impact Solutions I&II, and International Power Plc. During his 12 years at NRG Energy, David led the company from Chapter 11 to a Fortune 200 company. He is a frequent speaker on opportunities for accelerating the energy transition and was named the Energy Industry “CEO of the Year” by EnergyBiz in 2010, top CEO in the electric utility sector by Institutional Investor in 2011, and “Entrepreneur of the Year” by Ernst & Young in 2010. Prior to Generate, he served as Under Secretary for Infrastructure at the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE). David has previously served on the Boards of Heliogen Inc, Source Global, JERA Co. Inc., Saudi Electric Company, ACWA Power, El Paso and Tata Steel Ltd. He is a graduate of Harvard Law School and Princeton University.

It is easy to be disoriented by the swing from exuberance to pessimism that has defined the clean energy sector in recent years. Yet these moments are precisely when opportunity is greatest. Beneath the headlines are clear indicators of tremendous potential in the U.S. energy transition. The challenge is to separate fundamentals from sentiment, to acknowledge and fix the mistakes that we have made, and to chart a path to scale rooted in discipline, operational excellence, and commercial reality.

We must build best-in-class clean energy businesses at scale that operate with excellence, in technologies that are mature, and we need to rapidly commercialize ones that are not yet proven to attract institutional capital. Either way, scale needs to be our north star. Times when market exuberance subsides often lay the groundwork to consolidate.

This is not an industry for amateurs. Energy is a physical business based on steel, concrete, wires, and skilled professionals and technicians, not just spreadsheets and projections. Success, particularly now, requires knowing what questions to ask, where to find value, and how to recognize risks that aren’t always visible from desktop analysis. Only seasoned operators and experienced “hands-on” investors, with the right structures and the right capital, can successfully navigate these complexities. That is why I joined Generate: a company with a track record of building, operating, and financing the assets that shape both our present energy system and its future. At Generate, we are an operator-led platform that combines financial flexibility, structuring creativity, and deep market insight. We do that to accelerate the transition in a way that is both durable and impactful.

Like most of the sector, we made mistakes rooted in the euphoria of the early 2020s. We deviated from our operational roots and our expertise in structuring risk-mitigated project transactions to demonstrate our savviness as financial investors. While other investors had no choice but to act as pure investors, we were distracted from who we are and what we were good at. While that distraction led to poor performance in one component of our investment portfolio, we are built on a stable foundation of operating assets and private credit that are providing value for our partners, investors, and customers. Our focus moving forward will be to build on that foundation, which will give us an advantage in this moment.

From Exuberance to Pessimism

I’m an energy guy. I have run companies that invested in coal, gas, nuclear, and renewables. I also oversaw the commitment of over $100 billion in clean energy technologies running the gamut from fission to geothermal to carbon capture while at the US Department of Energy. The common element is power. Over the last 30 years, I have found the energy sector to be overly exuberant 80% of the time and overly pessimistic 20% of the time but I have never seen it simultaneously overly pessimistic about the present while ignoring the obvious reasons for optimism about the future. I believe that dislocation is our opportunity.

The goal is to spot and execute on investments that are valued based on current sentiment but have a clear line of sight to future opportunity. Right now, there’s a lot of noise telling people to stop writing checks. But this is precisely the time to invest in the infrastructure that will power the next twenty years.

The opportunity for immediate value and future potential is not new in the rare moments of pessimism for the energy industry. I was CEO of NRG Energy in 2009, at the height of the great recession when we acquired Reliant Energy’s retail electricity business for $287.5 million. Reliant was facing difficulties with credit and credibility but in the three months following the acquisition, the retail business under NRG generated roughly $350 million in cash, and it remains a flagship brand for the company to this day. Around the same time, First Solar acquired OptiSolar’s multi-gigawatt pipeline, including the 550MW Topaz project, and took on its development team. This proved to be highly lucrative and enabled its transition from a module manufacturer to a vertically integrated developer, which was a necessary strategic move at the time based on where the polysilicon market was headed.

The Great Recession followed the downturn in the early 2000s where similar dynamics were at play: U.S. M&A activity in renewable energy and utilities had fallen off coming out of the dot com bubble which coincided with gas-fired combined cycle overbuild across the U.S. While many players were retreating from the sector, GE moved in the opposite direction. Its acquisition of Enron Wind in 2002 marked the foundation of what is now one of the leading U.S. turbine manufacturers.

Of course, not all “contrarian” acquisitions done during previous “risk-off” periods turned out well. I believe the differentiating factor was, and still is, a maniacal focus on operational excellence and commercial opportunity. It’s why doing your due diligence in hard hats and steel-toe boots are as important to a successful infrastructure investor in times of distress as the most sophisticated economic models. You must know the industry and the assets – how they operate, what customers want, the regulatory environment they operate within, the communities they serve. That is what I think will drive our ability to take advantage of this moment in the energy transition.

The Opportunity

Despite the present environment of challenging policy, tight money, and operational shortcomings, our industry is set up for massive success. The key is to make sense of the dissonance. When viewed without politics and emotion, the demand for growth is undeniable, the policy environment is more stable than most think it is, and the mistakes we’ve made as a sector are correctable.

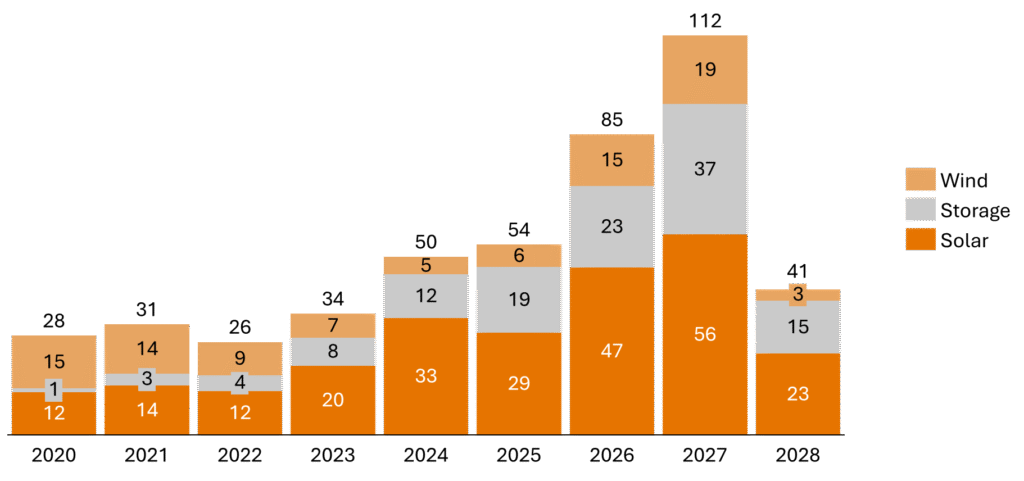

For the first time in nearly four decades, the US has an insatiable need for more power: as much as we can produce, as soon as we can, wherever and however we can produce it. Forecasted load growth is 2x the highest historical load growth. Much of the market is focused on how to serve rising data center demand, but this load growth also strains supply, which creates opportunities to serve non-data center customers seeking reliable, affordable power. The fundamentals of where this market is and where it is nearly certainly going favors clean power. Clean power technologies are the first in the queue and quickest to power, the most economic and flexible in terms of size and application. Interest rates are projected to fall, which boosts the competitiveness of renewable energy versus fossil fuel power generation. Indeed, U.S. solar and battery storage capacity additions over the next three years mark the industry’s largest ever expansion, with an estimated 250GW of wind, solar and energy storage due to be installed in the country from 2025 through to the end of 2027.

Figure 1: U.S annual capacity additions (GW)

The reality of power generation in the US is the primary reason why rumors of the death of the renewable industry are (way) overblown. But just doubling down on how we have done things in the past will not accomplish the dual goals of powering our economy while preventing climate change from being the largest destruction of value investors have ever faced. If we want to marry the opportunities of the next few decades with our transition goals, we must identify which technologies matter most, and which elements of a deal will most effectively accelerate deployment of that technology beyond the specific investment. We need a system to understand how to value capital, which opens pathways toward our inevitable goal of a decarbonized economy and that system needs to reflect how projects get built and operate in the real world – from supply chains, to where they’re sited, to how they are financed. That will require expanding beyond the current framework of climate change target-setting and reporting ecosystem, to instead identify the areas where investment can have the greatest impact in accelerating the pace of global decarbonization by considering factors essential to investment decision-making. Together with the Rhodium Group and CalSTRs, Generate has created the Transition Acceleration Framework in an attempt to do just that.

We also need purpose-built capital strategies. Many of these potentially accelerating technologies are currently stuck, unable to secure more venture or growth capital from their early backers but locked out of more rigid project finance markets. Scaling these technologies and accelerating the energy transition more broadly requires new structures that can effectively mobilize and channel institutional capital to where it is most needed. Solving this funding gap is perhaps the biggest challenge to solve today in sustainable finance. Generate’s Private Credit business helps channel institutional capital to where it is most needed in order to solve the biggest issues today in sustainable finance. Recent deals include our $200 million loan to build the first steel micromill in California in 50 years and our recent $100 million partnership with leading data center provider Soluna to source power from otherwise curtailed renewables. Moving projects from equity financing to debt is the key financing element of scale. While the capital markets are not creative spaces, they favor well-designed structures that protect downside risk. That is the opportunity for credit investors willing to do the work to help bring scale earlier in the process.

At the Department of Energy, where I was Under Secretary for Infrastructure from 2023 to 2025, we committed more than $100 billion of loans and grants to some 5,000 recipients, spanning multiple asset types, technologies and varying stages of commercialization. The prospects for many of these companies and projects is uncertain. What is clear is the clean energy industry can no longer count on this type or level of government support. That money will have to come from the capital markets and the sooner we can identify ways to make traditional capital comfortable with investing in these assets the sooner we will be successful in the transition.

Investor Capabilities

Moments of opportunity like this can fall away quickly if the financiers of the clean energy sector don’t coalesce around and fund the strongest players. To do this effectively, our investment firms must have three core skills: operational excellence, structuring creativity, and market intelligence that mirror the qualities of the companies we need to invest in.

Many firms are not set up to understand, let alone manage, the inevitable operational challenges that arise as you build and operate any hard asset, much less the scaled-up, multi-site construction programs that many in our industry embarked upon in the heady post IRA days. If we improve operationally, we will win because we are already ahead of the curve on costs. We need more hands-on execution in the field by skilled workers, capably led by managers on the ground not back in headquarters or sitting in high towers of finance. In short, investing and succeeding in an asset heavy industry is both blue and white collar and if you can’t speak effectively to both, you’ll make costly mistakes. When I do due diligence, I would rather spend 50 bucks on beers with a construction site manager than $500k on a consultant to know if something is worth investing in, what the challenges are, and if the investment will be successful. You need to be on the ground, and you need to know what to ask and where to look.

Operational excellence is key, but financial acumen and structuring expertise is essential to the proper allocation and mitigation of risk in infrastructure financing, enabling protection and meaningful upside. Having structuring flexibility allows for better and timely engagement with the variety of opportunities in the market. Many opportunities will only be undervalued for a short period of time before the market corrects and investors offering flexible capital and a variety of deal structures will be better able to get ahead of this. Generate has no net losses in 9 years of strategic credit investments across $1.2 billion of invested capital by adhering to a few core investment principles such as bilateral origination, being a sole lender, bespoke covenant packages, an owner-operator capability and having multiple exit paths. As an example, in 2020 Generate led a small group of experienced climate investors in a $600M corporate loan to finance the development, construction and operations of over 2GW of solar and 1.5 GWh of battery storage in California and Texas. This deal, and follow-on transactions with Intersect, unlocked a novel offtake strategy which mitigated downside risk but provided access to upside through merchant exposure that materially increased capital availability in the sector. The flexible, scalable facility also accelerated the buildout of one of the nation’s largest IPPs and hyperscale energy providers: Intersect is now a top-five solar developer in the U.S. The deal involved a senior secured lien on the parent company, broad negative consent rights, robust project-level coverage ratios, a scalable borrowing base, and key man provisions.

Some investments should sit on balance sheets where you can avoid the tension associated with holding long life assets in short-term funds; others are better suited for funds whether blind pool, seeded or a fund of one. Developers may favor joint development agreements, a development services agreement or joint ventures. The key is tailoring the financial solution to the need of the deal.

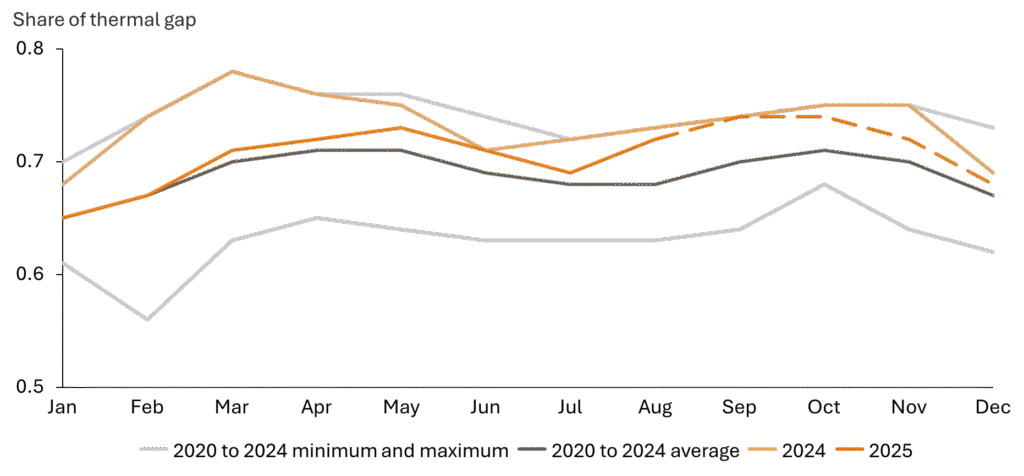

Finally, there is market knowledge and system understanding. Energy markets are deeply complex. Understanding the dynamics that motivate them – from complicated technology stacks to different market constructs – is key to investing successfully. The U.S. electricity grid is often named as one of the greatest engineering achievements of the 20th century. Of course, the problem is that we are a quarter of the way through the next century and the grid is struggling to adapt to new supply and demand signals and resources. There is not a choice between renewables and fossil energy as many headlines suggest. The current and future system will be made up of renewables, baseload, mid-merit, and peaker plants each playing their role in creating the reliability and affordability that the country demands. And the market will determine the mix. While coal and gas can often be in harmony, they are also fierce competitors. Indeed, the dethroning of King Coal during the first Trump Administration occurred not because of environmental pressure from renewables, but rather because of price competition from natural gas. And that competition continues (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Natural gas share of the thermal gap

The Goal: Effective Consolidation

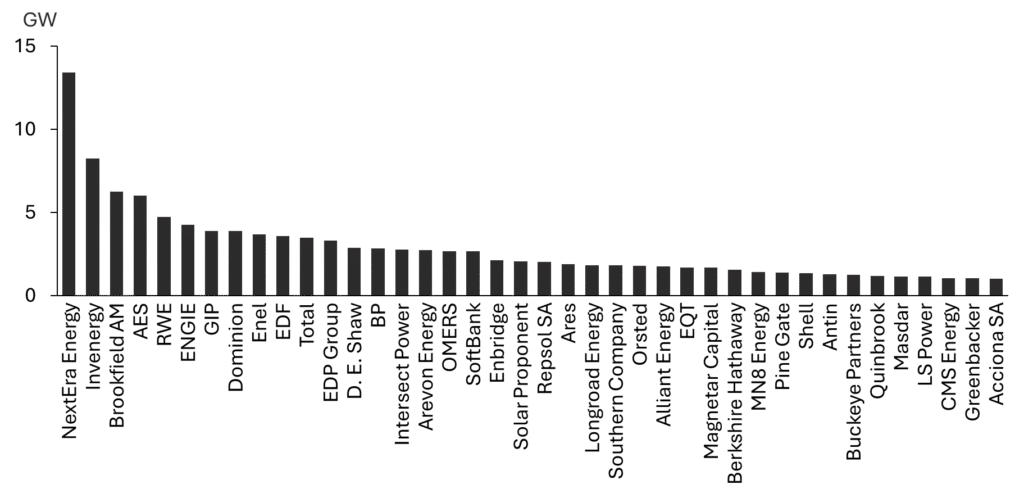

The thermal IPP sector in the 2000s went through a wave of post-bankruptcy combinations that created today’s dominant national platforms. The renewable and distributed power sectors are now poised for a similar round of consolidation. Clean energy remains very fragmented: the top 20 disclosed owners of both operating and in-construction solar assets in deregulated U.S. markets control 49% of the market.

Figure 3: U.S. operating and in construction solar assets in deregulated U.S. markets by owner

Source: Orennia

Being frank about the barriers to consolidation across the various clean energy subsectors, we need to appreciate that many of the companies in our space remain under the control of the original entrepreneur/founders, a cohort which stereotypically has a strong aversion to subsuming the companies they founded into another.

If companies across our subsectors were publicly traded, the market itself would act as a centripetal force towards industry consolidation. But they are largely privately held, funded by private sources of capital. As such, it is up to us, the providers of that private capital, to force industry improvement, through consolidation and otherwise.

Outlook

To truly understand the opportunity in front of us, we need to be honest about our mistakes. The sector allowed ambitious growth and climate aspiration to cloud the need to master business fundamentals in a high growth/easy money environment. It turned out that a lot of our emerging clean energy companies, however exciting their technology or business model, lacked these fundamentals and were too slow to realize. While they were on the right side of history, they were often wrong on what it takes to build solid companies in a durable industry. Climate may well be the most important social issue in human history, but the primary solution to it is fundamentally an economic problem.

That is when the “capital squeeze” began. As macro conditions changed, and the lack of exits at asset and corporate level became clearer, many allocators began to have doubts about the prospects for the sector, or at least the firms they had invested in. Public renewable companies have underperformed independent power producers and regulated utilities as investors price in pressure from rising rates, tariffs, and tax policy changes. From January 2024 to July 2025, public renewable energy companies are down 11%. The S&P 500 is by contrast up 32%, and a basket of “traditional” IPPs is up a staggering 233%. New equity capital for corporates dried up as few exits have occurred, and many platforms became highly levered.

Our priority today is to invest in sound projects, sponsored and implemented by well-run companies focused on the fundamentals not just of development but of building and operating their assets and marketing or hedging the output. These companies and projects need to have a clear path to scaling to greater importance and more sizeable impact. That will often come from consolidation. This is where the climate imperative rests right now. Thanks to the outgoing tide of unfavorable politics and constrained capital, the opportunity exists for investors who know the market, understand how to mitigate risk and are willing to get their hands dirty.

The dynamism of our capitalist system has always been predicated on creative destruction. Unfortunately, our sector has been struggling through a period of value destruction. It is time for all of us in the clean energy space, financiers and asset owners, entrepreneurs and technologists, contractors and operators to work together to turn away from creative destruction to creative construction, a pivot best achieved through industry consolidation.

More insights

Industrial Decarbonization: How Thermal Storage Can Electrify Heat at Scale

Investment in thermal energy storage has accelerated in recent years as technical progress and customer demand have improved project bankability. Since 2020, sector funding has grown and shifted toward later-stage investors, reflecting greater confidence in TES’s readiness for commercial deployment.

Read moreConsolidation: The Pathway to Enduring Impact

It is easy to be disoriented by the swing from exuberance to pessimism that has defined the clean energy sector in recent years. Yet these moments are precisely when opportunity is greatest. Beneath the headlines are clear indicators of tremendous potential in the U.S. energy transition. The challenge is to separate fundamentals from sentiment, to acknowledge and fix the mistakes that we have made, and to chart a path to scale rooted in discipline, operational excellence, and commercial reality.

Read moreMeeting load growth with clean, flexible power

In the wake of the One Big Beautiful Bill, load growth remains a clear and steady tailwind for renewable energy. Renewables remain the cheapest source of power and the quickest to install, ensuring a bright outlook for the industry despite the shortened available window for some tax incentives. Over the last twenty years, annual investment in renewable energy in the U.S. increased from $5 billion to $100 billion (BloombergNEF, 1H 2025 Renewable Energy Investment Tracker). Compelling economics and flexible demand has the potential to unlock even greater investment in the sector: powering new load with electricity that would otherwise be wasted boosts project economics, ensures quick access to power, and delivers system-wide benefits.

Read more