BIO

Logan Goldie-Scot is a VP of Research and Impact at Generate Capital, responsible for building and communicating the firm’s information advantage. He is focused on developing proprietary insights relating to Generate’s six core sectors, while supporting market-wide coverage and origination efforts.

Prior to Generate, Logan joined BloombergNEF in 2010 and was Head of Clean Power research when he left in 2022. This was a 30-person group spanning solar, wind, energy storage and power grids. At BloombergNEF he previously worked as a solar analyst, built and led the Energy Storage team, and developed the firm’s first clean energy Index and ETF, in collaboration with Goldman Sachs. Logan is a regular writer, speaker and conference panellist on topics relating to the energy transition. He has an MA (Hons) in Arabic from Edinburgh University and in 2019 completed executive training in Supply Chain Management at Stanford GSB.

Data centers: shortages, constraints, opposition, choices

Politics, policy and markets

Our favorite articles and reports from the last month

Constructive interference

The U.S. power grid is currently a study in constructive interference, a phenomenon where separate waves meet, their peaks align, and they merge into a single, amplified force. Capacity and generation shortages, the elevation of affordability to the center of politics, community opposition, and concerns about emissions and reliability are powerful dynamics individually. Together they may force long-lasting changes to the U.S. power systems, as proposed wholesale changes across PJM this month illustrate.

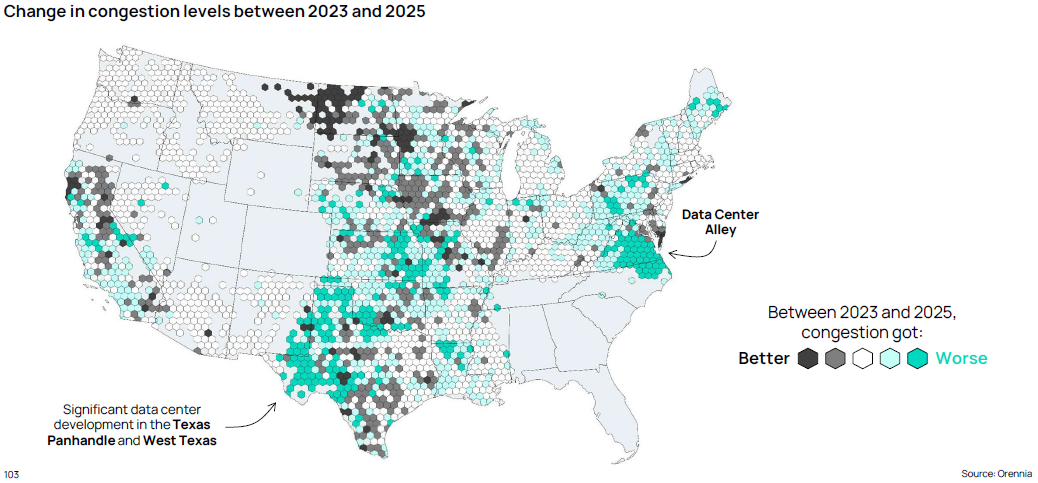

Transmission is congested

The electrical transmission system in the U.S. is jammed up, and congestion across much of the country is worsening not improving (Orennia).

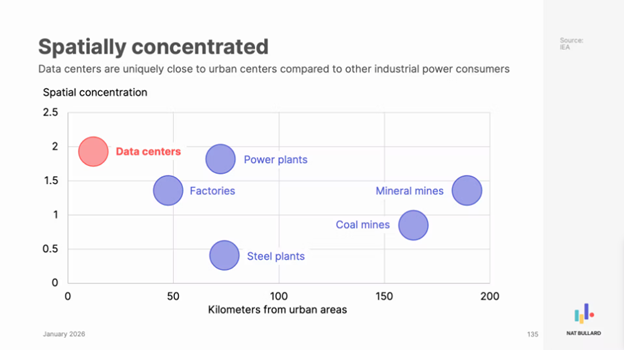

In part, this is because spare grid headroom has been exhausted in recent years. Data centers also tend to be located closer to urban centers relative to other large power consumers (Nat Bullard), which narrows the scope of available sites to choose from.

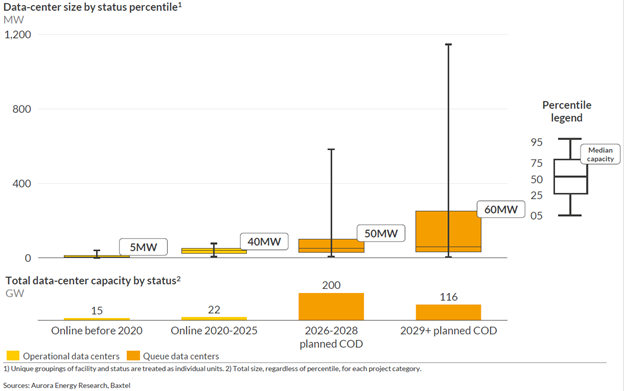

Data centers also tend to be significantly larger than the large-loads that came before them, and they keep growing. With capacity headroom, smaller loads could interconnect with few network upgrades required. These larger loads not only pose a challenge from higher demand straining the grid, but require immense grid upgrades to ensure reliability under contingency conditions (Aurora Energy Research).

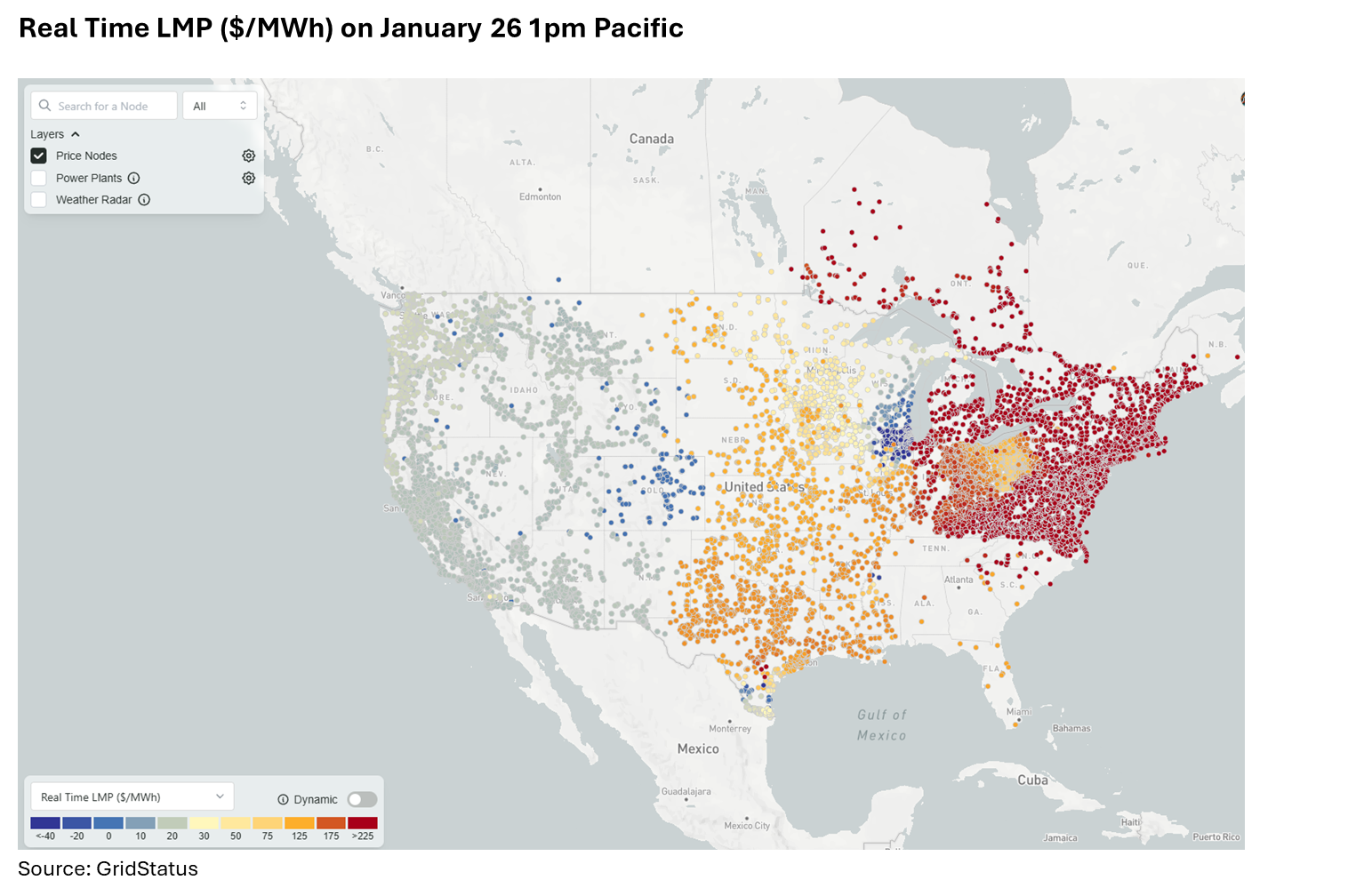

Finally, the U.S. grid remains fragmented which both limits its ability to manage extreme weather events and to decarbonize. The concept that you want a grid that extends further than the weather. The impact of Storm Fern was exacerbated because the Eastern and Western Interconection are physically asynchronous. Spot the seam on the map.

Short on generation and capacity

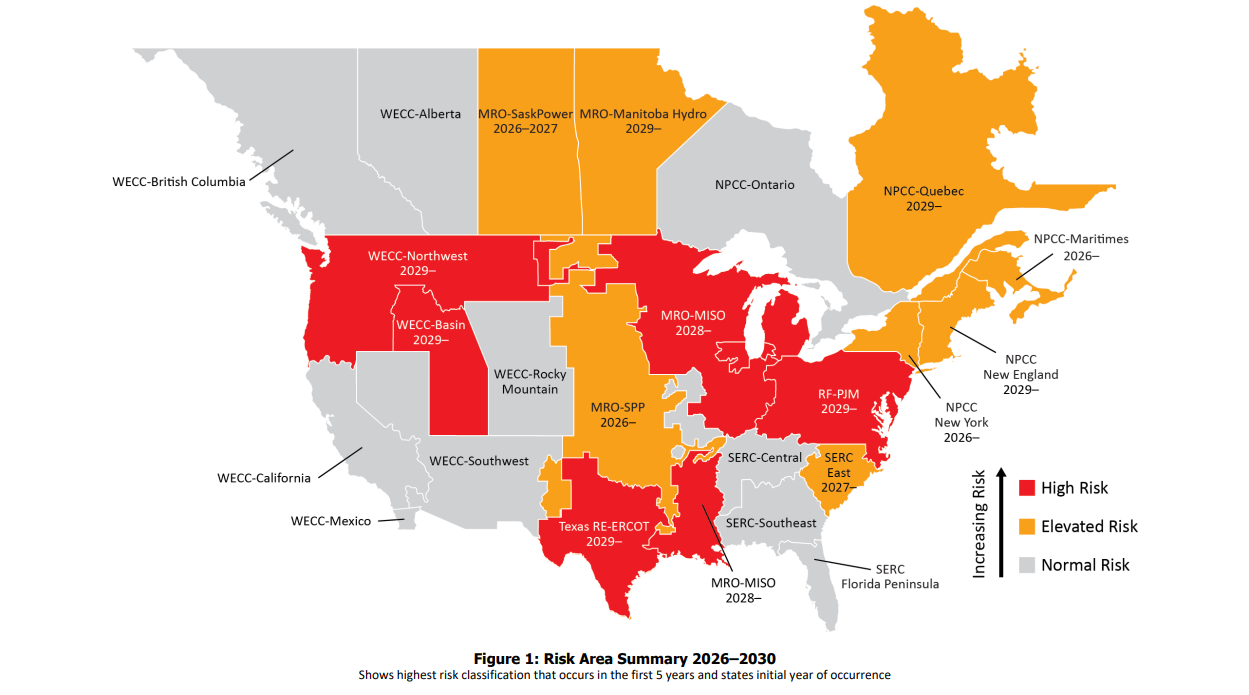

New generation and capacity is not coming online quickly enough to keep up with demand. The latest NERC Long Term Resource Adeqacy report finds that 13 of 23 assessment areas face resource adequacy challenges over the next 10 years (NERC). The report is somewhat charged, and not always accurate (link) but it’s clear we need to build a lot more generation and battery capacity to keep up.

A possible outcome of the race to meet large-loads may be a complete rethink of how electricity systems are designed. This may seem fanciful but is not unprecedented, with examples from natural gas and water showing potential alternative approaches. “Electricity systems have generally been premised on the assumption that utilities have a duty to serve customers, would meet demand at nearly all times, and would maintain sufficient capacity so that even peak demand periods could pass without curtailments or blackouts. For natural gas systems, the duty to serve was also part of common law and regulatory history, but it has been largely replaced by a contracts- and payment-based system, particularly with regard to non-residential customers.” (Allocating Electricity). If it’s broke, fix it.

Flexibility is possible, but not certain

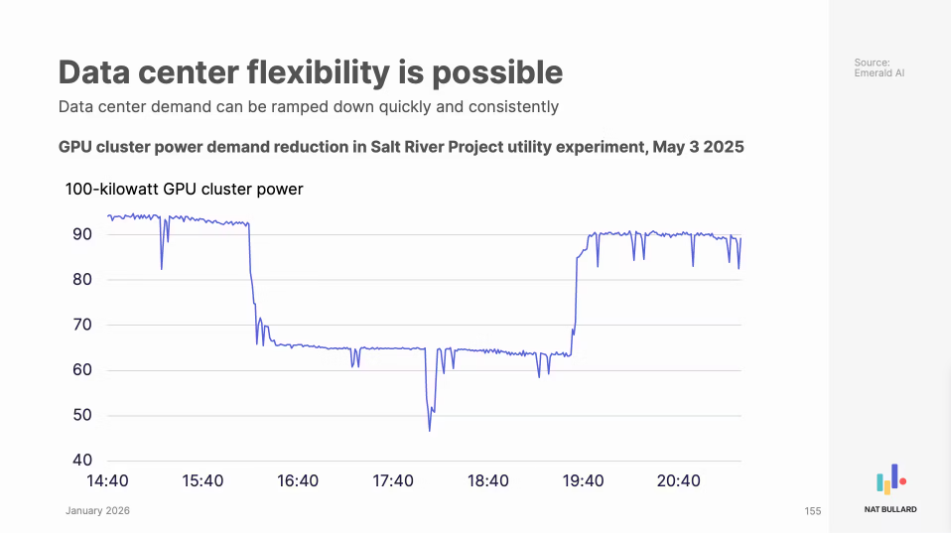

Pilots have shown workload flexibility is possible, but larger data center customers at least remain broadly resistant due to the high opportunity cost; and utilities are mistrustful. A few notes from the archives on what could change this impression (Arushi Sharma Frank, Energy Hub’s Huel’s Test). Or, if hyperscalers don’t want to curtail, can they pay someone else to (The Ad Hoc Group).

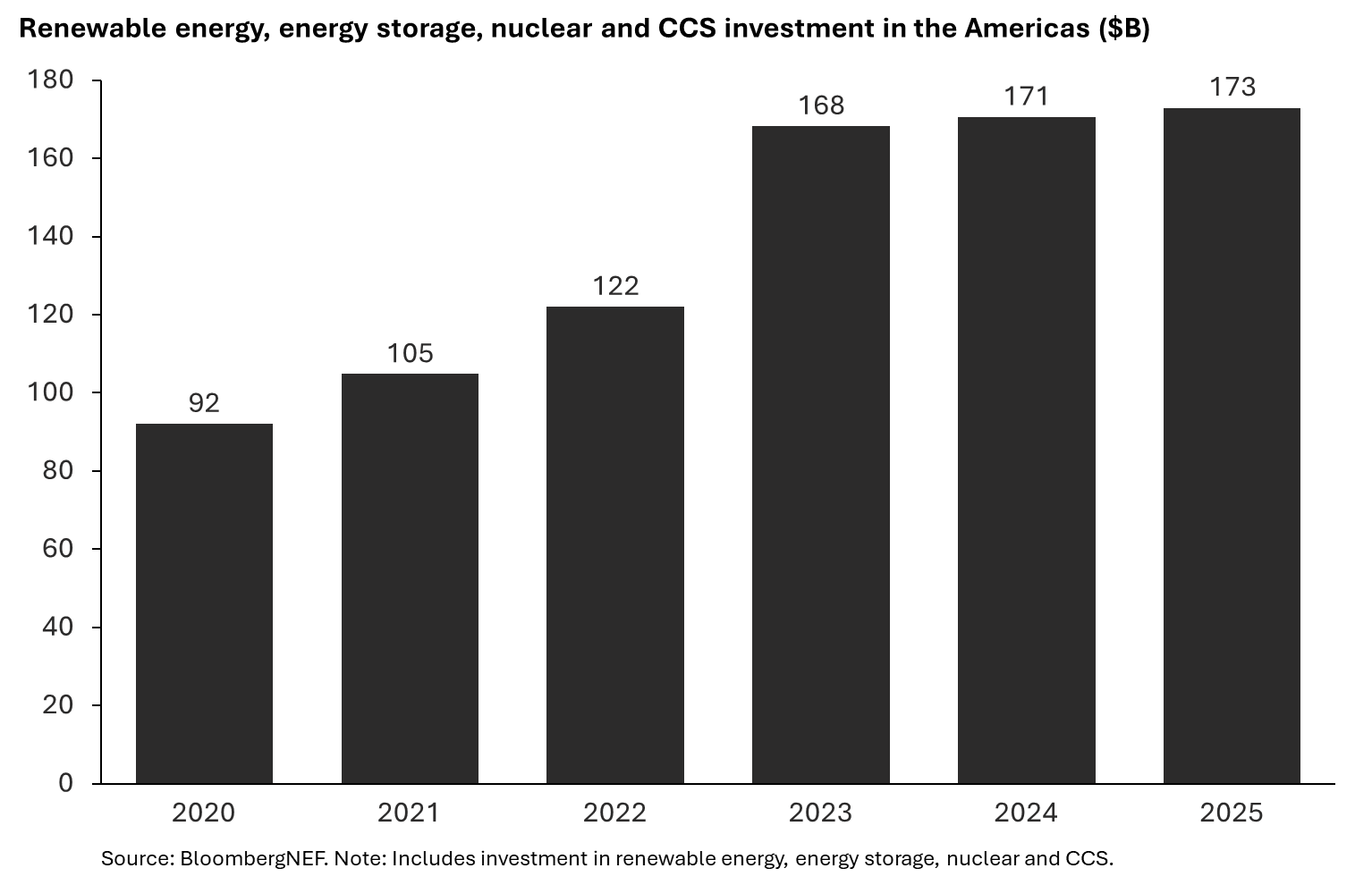

Investment in clean energy is flat

Despite the clear demand signal, countering headwinds in the U.S. are hindering clean energy’s ability to meet the challenge. 2025 was still a record year for clean energy installations across the country but at a time when investment needs to be accelerating, it is slowing. If you’ve made it this far, you likely have a good sense why.

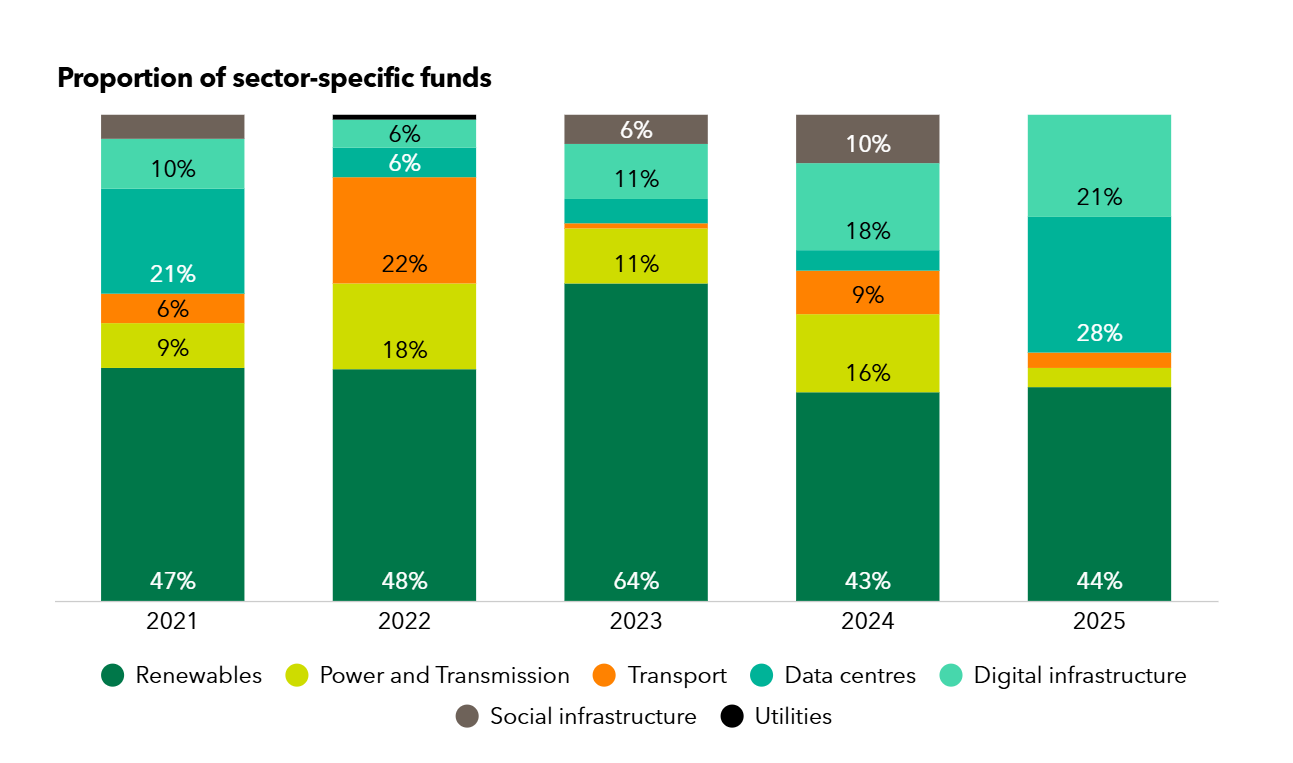

This for not a lack of capital raised: 2025 is the biggest year for unlisted, closed-end infrastructure fundraising, with $289 billion raised (Infrastructure Investor). Of the sector specific funds, 44% were for renewables with an additional 28% targeting data centers. At the BloombergNEF SF Summit earlier this week, executives across panels reiterated their confidence in the fundamentals of the U.S. clean energy industry, despite the challenges.

Choices

These constraints require data center developers and customers to make choices. Of the many, two stand out. Clean or fossil (largely gas); Grid connected or onsite.

This is of course a radical simplication and one of the fascinating outcomes of the data center race is that the lines are increasingly blurry. The likely outcome involves a lot of renewables and batteries and further investment in gas; and a mix of onsite and grid-connected resources (often to serve a same site). For example, Pacifico Energy recently secured an air permit for up to 7.65GW of natural gas generation at a site in ERCOT with up to 1.8GW of battery storage and 750MWac of solar.

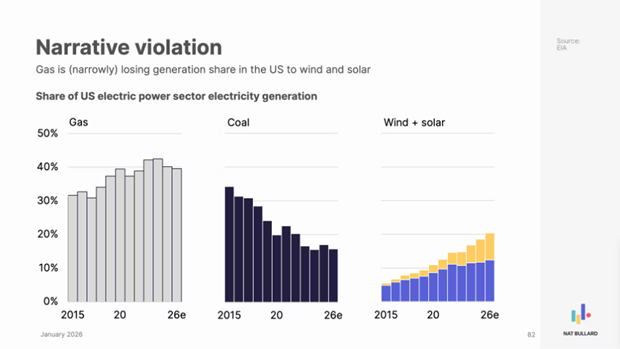

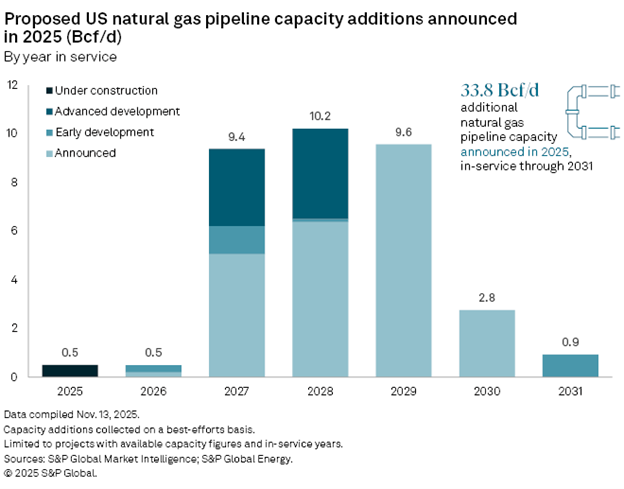

In terms of where things stand today: gas is (narrowly) losing generation share in the U.S. to wind and solar in the near-term (Nat Bullard). The large pipeline of announced gas generation capacity and pipelines relative to recent build will likely reverse this (S&P). “Constraints on supply from a maturing industry and pipeline bottlenecks make this next growth cycle look different than history — meeting this upcoming wave of demand will be more costly than the last.” (Morgan Stanley research). This cost is measured in dollars and emissions.

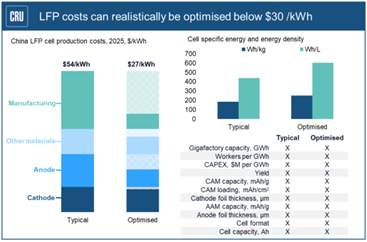

The dollar cost is partly because turbines are increasingly hard to get hold off, and are increasing in price. Meanwhile clean energy equipment show no sign of approaching their theoretical floor price. U.S. prices are somewhat disconnected from global prices due to ever-changing trade environment but the potential of cheaper products can’t be ignored forever. In just one tantalizing example, recent analysis from CRU, h/t Volta Foundation’s annual battery report, finds that LFP cell production costs can realistically be optimized below $30/MWh.

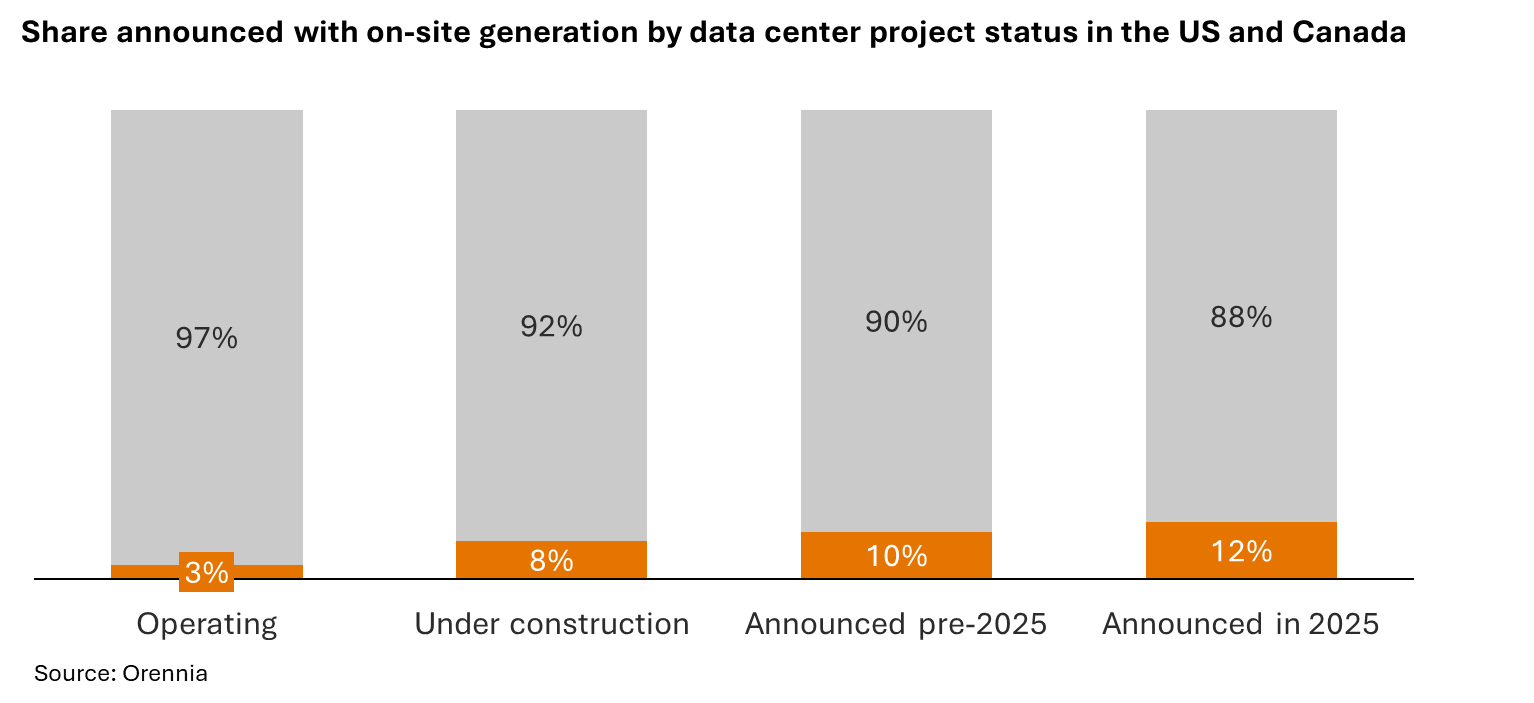

A second choice for many data center developers is whether to grid connect or to stay behind-the-meter. Some 12% of announced data center projects announced in 2025 have on-site generation to provide primary or supplemental power, versus only 3% of operating projects. This excludes diesel used for backup since otherwise the number would be closer to 100% already.

Onsite power may be the permanent solution for some firms but is more likely to be a bridging solution for most developers, whose primary long-term objective remains full grid integration as it becomes available. Essentially, most will pick the grid if it is a viable option. The onus is on energy developers to prove it is one.

Community engagement and opposition

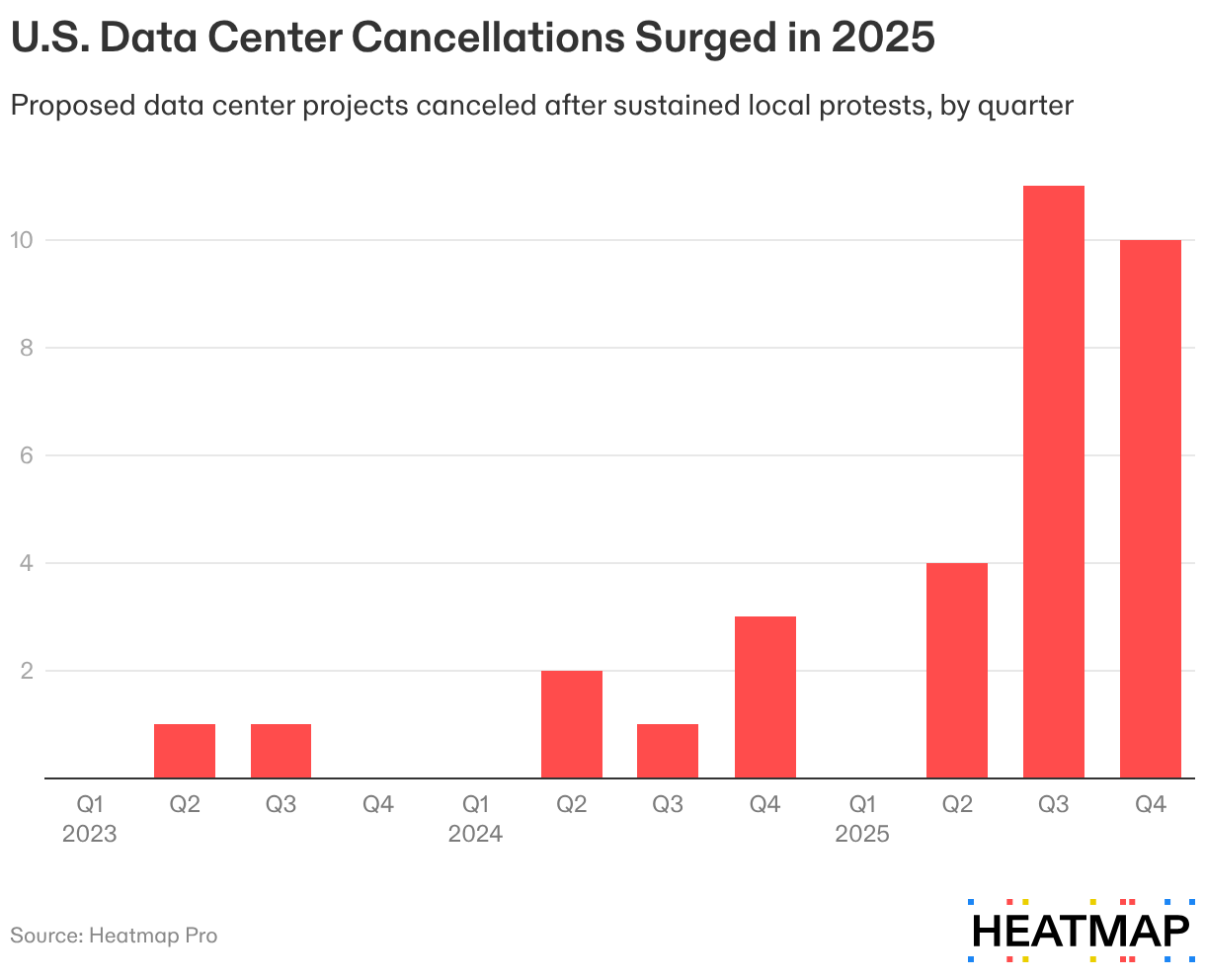

Data center executives at PTC in Hawaii earlier in month commented how community resistance now rivals power availability as a top concern (The Information). Data tracked by Heatmap Pro corroborates this: at least 25 data center projects, totaling 4.7 gigawatts of electricity demand, were canceled last year following local opposition. Deft community engagement has always mattered with energy development but perhaps now more than ever.

Policy notes

Since the beginning of the year, an orienting truth is taking shape: Politics drives policy, policy drives markets, and markets drive capital decisions. That may seem obvious, but after decades of flat, distributed growth on the grid, power pricing and delivery were hardly a topline political issue. The chain often started with policy decisions being made in overlooked forums fueled by deeply vested interests. Power’s political prime time is shifting how policy is made and how markets are developing.

The politics

Affordability has risen as a key political issue throughout 2025, driving Democratic victories in VA and NJ Governor’s races. This trend is continuing into 2026, with both parties putting the “affordability crisis” at the center of their platforms with 2026 midterm elections just a few calendar flips ahead.

Hyperscalers, recognizing these dynamics, are making announcements focused on their commitment to “pay their way” and not pass costs onto residential consumers.

Microsoft’s “Community First AI initiative” pledges for all costs associated with new energy infrastructure, covering data center power costs and capacity expansions with local utilities. President Trump chimed in celebrating the announcement and insisting that big tech “pay their own way,”

OpenAI similarly announced its “Stargate Community” initiative focused on preventing electricity cost increases when building data center projects. That means funding dedicated generation and grid upgrades for each campus.

The policy

NJ Governor Mikie Sherril signed executive orders to both reduce electricity rate costs and to accelerate solar and storage development in order to grow electricity supply. The measures include freezing electric rates, identifying new ways to expand customer bill credits, and recommending updates to modernize utility regulatory frameworks.

In Virginia, Georgia, West Virginia and Massachusetts – all data center hot beds – an onslaught of bills have been introduced on these topics including proposed legislation to accelerate clean energy build out, take advantage of surplus interconnection, and finding ways to reduce costs on customers.

Policy, like molasses, flows very slowly but the sheer volume of these proposals and the emerging, near universal consensus from both parties, the largest drivers of power increases, and the core regulating may just accelerate outcomes.

It is, of course, very complicated. Ultimately the decisions made by multiple policy making entities – state legislatures, wholesale markets, and FERC – will dictate how data centers pay and what burden falls on customers.

The markets

In wholesale markets, paying full costs does not preclude an increase in prices for customers absent other market reforms. Wholesale price volatility and capacity outcomes eventually show up in retail bills. Further, cost of regional and interregional transmission upgrades are allocated based on longstanding methodologies that socialize the costs. Changing these structures requires speed and coordination among policy making bodies that we have not seen in recent memory.

This is playing out most clearly in PJM, the country’s largest energy market. A coalition of 13 PJM state governors, the White House and the PJM Board made waves in the debate over the last month. These announcements both acknowledged the need for backstop capacity procurement and for large load interconnection processes to both enable growth and protect ratepayers.

The PJM Board memo made some of these roles more explicit. For example, on the topic of making data centers pay for additional capacity, while PJM can allocate capacity procurement costs among LSEs, only state actors have the authority to dictate how those costs should be allocated to customers.

While there are so many issues facing regulators, one that is grabbing headlines is how large loads can “skip the line” and be prioritized for interconnection. PJM has proposed a fast-track process be completed by August 2026, that will require “large scale generation greater than 250MW” achieve COD within 3 years, in the same state as the load. States will still need to shape technology requirements, including how those interact with climate commitments.

Elsewhere, FERC just approved SPP’s novel plan for high-impact loads – High Impact Large Load (HILL) interconnection process to accommodate big loads quicker. For large new load (50+ MW) that comes paired with new generation (on-site or nearby), SPP will complete the grid interconnection study in ~90 days and get them connected far faster than the years-long norm. These projects must accept non-firm, conditional service and must cover their own upgrade costs.

Not to be overlooked, in Texas 225+ large-load projects (from data centers to crypto mines) flooded the queue last year, far beyond the ~40 projects/year the system was designed to handle. ERCOT is introducing a new process to evaluate many big interconnection requests simultaneously rather than one-by-one while the Texas Commission continues to shape the regulations from their large load reform legislation from 2025 (SB6).

What we're reading

Davos 2026: Special address by Mark Carney, Prime Minister of Canada (link)

Two pieces from Noah Smith on the U.S.’ relationship with China. One, from the archives, dismisses the stereotype that China “is a patient, far-sighted entity — as compared with the impulsive, short-sighted West”. The second makes the case that “Chinese EVs could be just the thing to save Detroit from its own short-termism, the way Japanese compact cars were in the 1980s.”

Why AI Data Centers Can’t Get Power by David Riester at Segue. Red tape, transmission and deliverability, power scarcity.

A proposed fix to federal permitting uncertainty: extend the same lease cancellation protections that oil and gas developers have enjoyed since 1978 to every form of energy development (The EcoModernist)

Steven Sinofsky’s write-up of CES: The future is here.

Michael Cembalest at JP Morgan’s annual outlook focused on four medium term risks. US power generation constraints, China scaling the moat on its own, Taiwan and a “metaverse moment” for hyperscaler profits after $1.3 trillion of capex and R&D.

Very much in the “Other Interests” category but 15 charts on autonomous vehicles from The Driverless Digest

More newsletters

January 2026 Newsletter

The U.S. power grid is currently a study in constructive interference, a phenomenon where separate waves meet, their peaks align, and they merge into a single, amplified force. Capacity and generation shortages, the elevation of affordability to the center of politics, community opposition, and concerns about emissions and reliability are powerful dynamics individually. Together they may force long-lasting changes to the U.S. power systems, as proposed wholesale changes across PJM this month illustrate.

Read moreDecember 2025 Newsletter

How 2025 sets the stage for 2026. A review of AI, interconnection reforms, clean power and large load growth.

Read more